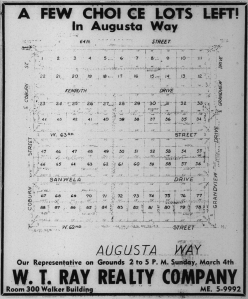

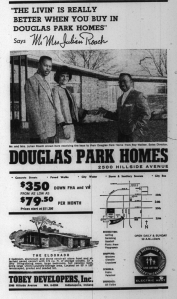

An Augusta Way advertisement from 1956.

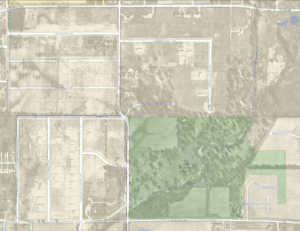

Perhaps the best-known African-American suburbs in Indianapolis were centered along Grandview Drive in the city’s northwest side. In 1946 Henry Greer (1894-1996) and wife Della Wilson Greer (1890-1979) moved into a newly built home at 6309 Grandview Drive, an area that was then mostly in the midst of farm fields and undeveloped property. A few farmhouses were scattered throughout the area as well as a couple houses along Grandview Drive (for, instance, the home at 6404 Grandview Drive appeared on the 1937 aerial view of the neighborhood, and the stables at 1005 West 64th had been built). The surrounding properties would eventually be the heart of a series of predominately African-American suburbs that went under a wide range of names, including Augusta Way, Grandview Estates, Grandview Terrace, Northshire Estates, and Greer-Dell Estate. This page links to a PDF inventory of some of the earliest residents in the Grandview neighborhood as a preliminary step examining who built and settled these homes and how long households lived in the neighborhood (compare a similar inventory for the earliest residents of Flanner House Homes).

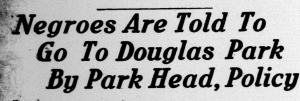

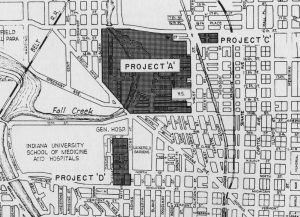

The Greers built their home on Grandview in 1946. Henry Greer opened a liquor Store on North West Street in December, 1935, and his wife Della Wilson Greer was an art teacher at Crispus Attucks High School, where she taught for 20 years beginning in 1936. Dr. Edward Paul Thomas (1920-2001) and Ruby Leah Thomas (1921-2006) became their neighbors around 1952, settling in the home immediately south of the Greers at 6235 Grandview Drive. At around the same time the fields between Michigan Road and Coburn Avenue were densely built up with suburban homes, but to the east of Coburn the area remained open fields until about 1955. Those fields east of Coburn became the Augusta Way subdivision, which was among the city’s earliest African-American suburbs. The homes west of Coburn Avenue remained nearly exclusively White through the 1950’s, but lots west of Coburn began to appear in the Indianapolis Recorder by 1960, which suggests the neighborhoods to the west of Augusta Way began to integrate in the 1960s.

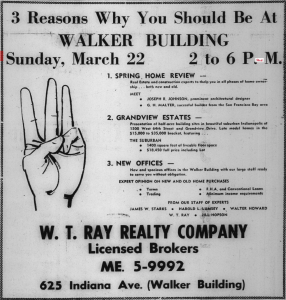

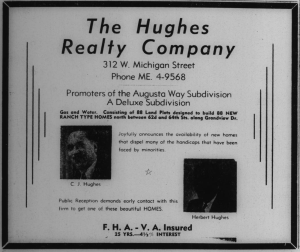

The earliest ad for Augusta Way appeared in December, 1955 from the Hughes Realty Company.

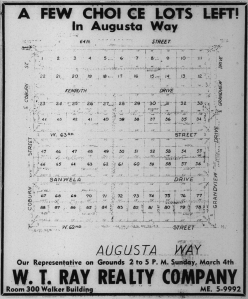

The earliest subdivision name in the neighborhood was Augusta Way, perhaps invoking the little town of Augusta that lay north along Michigan Road. Augusta Way was first advertised in December, 1955 by Hughes Realty, who offered up 88 lots for the construction of ranch homes. The developer of the subdivision, George W. Malter, named W.T. Ray as a sales agent in February 1956. Ray almost instantly became the primary agent handling Augusta Way’s sales, offering up lots for $500 down. A 1956 aerial photograph appears to reveal construction in only one lot in the subdivision, which became 1605 Kenruth Drive and was the home of W.T. Ray. A block away and built at nearly the same time was Earl and Vanessie Seymour’s home at West 64th Street, which was advertised with a picture in November, 1957.

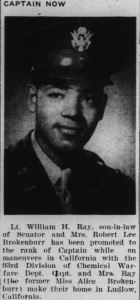

W.T. Ray had a profound influence on the African-American suburbs as one of Indianapolis’ most active real estate professionals, but he was also was among the most influential figures in Indianapolis’ postwar African-American housing and civil rights movement. The Connecticut native spent much of his childhood in Caldwell, New Jersey, where his father William was the superintendent of an apartment house; the Rays were the sole African-American residents among 14 households including neighbors from Russia, Lithuania, Poland, and Germany. Ray studied business administration at Oberlin College and then Western Reserve University in Cleveland, and he was working in retail sales when he enlisted in the Army in 1941. Ray served in the South Pacific in World War II, where he was in the segregated 93rd Division’s Chemical Warfare unit.

In September 1942 Ray married Alice Brokenburr in Arizona, where Ray was stationed at Fort Huachuca as a Chemical Warfare instructor. Alice was the daughter of lawyer Robert Lee Brokenburr, who represented Madam CJ Walker and became Indiana’s first African-American state Senator in 1940, serving four more terms before he retired in 1964. Alice Brokenburr attended Alabama State Teacher’s College, where she trained as a music teacher, and taught at Florida A&M in the early 1940s. Ray became a real estate agent upon his return to Indiana after the war. In 1947 Ray became President of the Indianapolis NAACP chapter. Ray would become the first licensed African-American realtor in Indianapolis, and he served as an Executive Assistant to Governor Otis Bowen between 1973 and 1981.

Augusta Way homes began to be settled in 1959, but by that time homes on 64th Street, Grandview, and Greer-Dell had been completed. Henry Greer apparently divided acreage adjoining his home and created Greer-Dell Drive, which was advertised at least once as Greer-Dell Estates. In 1956, three homes were being completed on the south side of Greer-Dell Drive and two on Wood Knoll Drive. On West 64th Street, about 11 homes had been completed in 1956. For instance, long-time Madam Walker company Secretary Violet Reynolds and her husband David appeared in the city directory in 1957 at 1559 West 64th Street.

Eventually as Augusta Way lots were purchased with homes still being built until about 1967, subdivisions were opened north along Grandview Drive and north of the newly constructed Grandview Elementary School. Some lots were advertised in October, 1962 as Grandview Estates; additional lots were sold as Grandview Terrace in July, 1965; and others were sold as Northshire Estates in April, 1966.

Most city directory entries in these neighborhoods do not begin until 1957, though a few appeared earlier. This table (PDF) lists the earliest heads of households who appeared in the city directory for most of the streets in Augusta Way, including 64th Street, Kenruth Drive, 63rd Street, and Sanwela Drive as well as some portion of Grandview Drive; it also includes Greer-Dell Drive and 65th Street. Many of the earliest city directory entries in Augusta Way date to 1959, but by then some residents may have been in their home a year or two and some households had already appeared in the directory.

Original research in this post was conducted by Derek Blice (Kenruth Drive), Johanneson Cannon (Grandview Drive), Tarena Lofton (Greer-Dell Drive), Jared Meunier (65th Street), Kyle Huskins (Sanwela Drive), Andrew Townsend (63rd Street).