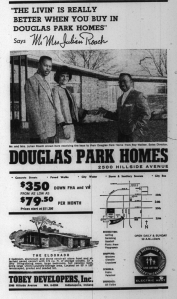

Julian and Thelma Roache appeared in this January, 1963 advertisement for the Caroline Avenue home where they would live for 40 years.

In January, 1963 Julian and Thelma Roache appeared in the pages of the Indianapolis Recorder celebrating their new home at 2701 Caroline Avenue. The advertisement was one of a series featuring new suburbanites who had moved into one of Tobey Developers’ eastside communities, Douglas Park and Kingsly Terrace. Among the Roaches’ neighbors appearing in the ads were Leroy and Winnie Herndon at 2609 Hillside Avenue and Roy and Mildred Gibson at 2908 Brouse Avenue (the Kingsly Terrace neighborhood). It is the stories of these neighbors and their paths to Indianapolis’ suburbs that we hope to illuminate in the Spring 2016 semester in the African-American Suburbia project.

In the first three decades of the 20th century, most of Indianapolis’ African-American arrivals in the Great Migration came from Kentucky. For instance, Julian Roache Jr.’s father Julian Sr. was born in Herndon, Kentucky in 1892, where he was a farmer. Julian Jr.’s grandfather Mercer was born in Virginia in 1844 and almost certainly grew up a captive. Mercer Roache moved his family to Kentucky immediately after the Civil War, where they lived into the 1920s. Julian Roache Sr. and his wife Rosa came to Indianapolis around 1926, when Julian Jr. was born.

Julian’s wife Thelma had been born in Danville, Illinois in 1918, where her father Phenious Smith was a coal miner. Phenious had married Almeter Render in Indianapolis in 1911, and the family apparently lived in Indianapolis as well as Illinois until the Depression.

Julian Roach Jr. married Thelma Smith Randle in January 1950. Julian worked at the Kingan and Company meat-packing plant, the massive 1862-1966 plant that was purchased by the Hygrade Corporation in 1952. In 1964 when Julian and Thelma first appeared living in Douglas Park at 2701 Caroline Avenue he was working as a beef boner at Hygrade. In September, 1963 Julian’s eastside neighbors Roy and Mildred Gibson also appeared in a Tobey ad for their home at 2908 Brouse Avenue, and Roy likewise worked at Hygrade.

Julian subsequently worked as a butcher at Kroger’s grocery store for at least 30 years. In 2001 he was still living at the Caroline Street home, two years after his wife Thelma had died. A year later he had finally moved from his Caroline Street home to a near-Westside home owned by his sister-in-law, Thelma’s sister Maxine. He had lived in the Caroline Street home for 40 years.

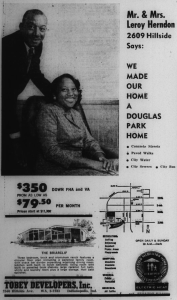

In September, 1963 Leroy and Winnie Herndon appeared in an ad celebrating their new home on Brouse Avenue.

Leroy and Winnie Herndon appeared in a September, 1963 Tobey Developers’ ad for their home on Hillside Avenue. Leroy was born in Rockfield, Kentucky in 1921, and like many African Americans he served in World War II. Many of the Herndons’ neighbors secured Veteran’s loans, and many local African-American realtors advertised the availability of Veteran’s Administration loans (though it is not clear that Leroy and Winnie purchased their home with a VA loan). Herndon had enlisted at Indianapolis’ Fort Benjamin Harrison in March, 1943, and he was employed as a general laborer at the Fort Harrison Finance Center from about 1955 until 1976. The Herndons appeared as a retired couple living at 2609 Hillside Avenue in the 1990 city directory, and Leroy died in January, 1992. When Winnie died two years later, she had lived there for 30 years, and their neighbor Mildred Gibson lived at her Brouse Avenue home until 1987.

These glimpses into a few of the first families moving into the eastside developments are of course simply impressionistic, and it is not clear how Tobey Developers chose these particular families to feature in its advertising campaign. It is also quite possible that different patterns may emerge in northside communities. Yet as an initial insight into the eastside communities, all of the couples who appeared in Tobey Developers’ ads were long-term residents of the newly constructed neighborhoods. All of the couples were solidly working-class families, and most were the first generation in their family to grow up in Indiana. While many of the families living along Grandview Drive and in Augusta Way on the northside were part of numerous social groups, the couples in the Tobey Developers’ ads were actually not especially prominent in the local social columns. In Spring semester the students in the class should begin developing a much more systematic picture of these neighborhoods and residents.