by Kyle Huskins

In July, 1926 the Indianapolis Recorder complained that they could only reserve space or visit the city’s “Jim Crow” park, Douglass Park. This would remain true into the 1960’s.

Douglass Park is one of the most historic parks in Indianapolis. It is named after the African-American intellectual Frederick Douglass, who played a pivotal role in the abolitionist movement and is one of the most recognizable African-American scholars of his time. The name of the park honors his memory and there is a mural of him on the wall of the Family Center. Douglass Park is located on the east side of Indianapolis. The address is 1611 East 25th Street in the midst of the Martindale-Brightwood community. Now the park is easily accessible from the Monon Trail and features a playground, tennis courts, picnic facilities, baseball diamonds, basketball courts, football fields and a paved fitness trail. During the summer months the pool opens and many eastsiders enjoy the pool facilities. Douglass Park also has a family center that provides surrounding youth with after-school programs and events for the community. The history of the prestigious park is a topic that has not gotten a lot of scholarly attention. Learning about the history of the park will enhance the level of prominence that this park has secured and acknowledge its service to the African-American community.

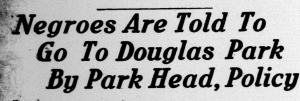

The Park opened in 1921, and after a 1941 expansion it today spans 43 acres. Much of the park’s heritage is linked to the city’s racial and discriminatory history. When Douglass Park was opened it was designated solely for African Americans, and African Americans were not allowed to attend other parks. In July, 1926 the Indianapolis Recorder reported that its representatives tried to obtain a permit to have a picnic at Brookside Park, but after being questioned excessively by the clerk they were denied times to hold the picnic. The paper’s representatives had attended prior events at Brookside Park and found their experience very enjoyable. After asking questions that the clerk could not answer, the clerk ushered them to the Superintendent of Parks’ office. Superintendent R. Walter Jarvis informed them that Douglass Park was the “Jim Crow Park” and he steadily insisted that Douglass Park was a nice area for its “colored citizens” (he had made the same argument in print in The Playground in 1923). The representatives from the Recorder did not obtain a permit for a picnic and were told by the superintendent that African Americans should go to Douglass Park to limit animosity.

This was not the only instance that this park saw some levels of discrimination. In July, 1950 the Recorder reported that the park board feared a “wooing wave” of romantic activity in the parks, and the board appealed to the police to “suppress the citizen’s public amatory proclivities.” The police increased their presence in the park, but the Recorder noted that while out investigating these claims, its reporter did not see any public misbehavior in the park. Such battles continued well into the 1960’s before the Indianapolis parks were desegregated.

Even though African American faced discrimination and segregation they made the best of a bad situation. Events and people came to the park in significant numbers. Douglass Park once had a skating rink that advertised regularly in the Indianapolis Recorder, and the park held many sporting events for people of ages. There was little league baseball at the park, golfing, and many social events at the park.

However, these facilities were often inferior to those at other city parks. For example, in September, 1926 the Indianapolis Recorder complained that “Jim Crow Takes Up Near-Golf,” lamenting the modest Douglass Park golf course. The paper recounted the plan to open a golf course in Douglass Park that was originally planned for just three holes; after some resistance, the parks planners agreed to fit six holes onto the golf course, which was eventually expanded to nine holes. The Recorder complained that these holes originally were simply tomatoes cans scattered about a field. Nevertheless, heavyweight world boxing champion Joe Louis would often golf at Douglass Park, along with champion golfer Ted Rhodes. Their arrival to Indianapolis would quickly buzz through the city and spark interest in golf in people that were otherwise disinterested. The Douglass Golf Club spawned many talented African-American golfers.

After looking into Douglass Park and the Martindale-Brightwood Neighborhood, the Eastside Better Business and Civic League kept appearing in the research. Members of the organization were successful in obtaining many public demands such as adequate street lighting, better bus transportation, donations to elderly men and women, and contributions to the Douglass Park and Hill Community Centers. For example, they handled Armin Graul’s donation. Armin Graul was a local businessman on the eastside of Indianapolis; he had a hardware store, one that my grandfather in later years frequented. Mr. Graul and his wife cared about the community and initially, in their will, they were going to leave $4,000 to Douglass Park to help fund events and sports leagues; however, in 1957 community members persuaded him that it would be better to do it while he was alive and donate $300 dollars a year for five years or until he died. The EBBCL handled Graul’s donation and Graul praised the EBBCL as one of the oldest active civic organization. Not only did the EBBCL help with fundraising they also held events, such as a Christmas Party for the kids in the community as shown here with this picture.

I am a native eastsider and I have frequented Douglass Park many times. I did not know the cultural history that was associated to the park. I believe that we can honor the people who helped make Douglass Park a key cultural African-American space by knowing the history of the park and understanding the legacy that it has within the community. This is African-American history that is often forgotten and is not readily shared. Public discourse in historic African-American spaces is pivotal to embracing and acknowledging the everyday challenges that many of our ancestors faced.

Reblogged this on The Ties That Bind and commented:

Great information regarding the origins of Douglass Park.

LikeLike

Awesome information

LikeLike