by Kyle Huskins

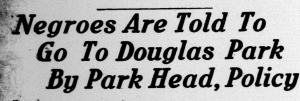

In July, 1926 the Indianapolis Recorder complained that they could only reserve space or visit the city’s “Jim Crow” park, Douglass Park. This would remain true into the 1960’s.

Douglass Park is one of the most historic parks in Indianapolis. It is named after the African-American intellectual Frederick Douglass, who played a pivotal role in the abolitionist movement and is one of the most recognizable African-American scholars of his time. The name of the park honors his memory and there is a mural of him on the wall of the Family Center. Douglass Park is located on the east side of Indianapolis. The address is 1611 East 25th Street in the midst of the Martindale-Brightwood community. Now the park is easily accessible from the Monon Trail and features a playground, tennis courts, picnic facilities, baseball diamonds, basketball courts, football fields and a paved fitness trail. During the summer months the pool opens and many eastsiders enjoy the pool facilities. Douglass Park also has a family center that provides surrounding youth with after-school programs and events for the community. The history of the prestigious park is a topic that has not gotten a lot of scholarly attention. Learning about the history of the park will enhance the level of prominence that this park has secured and acknowledge its service to the African-American community.

The Park opened in 1921, and after a 1941 expansion it today spans 43 acres. Much of the park’s heritage is linked to the city’s racial and discriminatory history. When Douglass Park was opened it was designated solely for African Americans, and African Americans were not allowed to attend other parks. In July, 1926 the Indianapolis Recorder reported that its representatives tried to obtain a permit to have a picnic at Brookside Park, but after being questioned excessively by the clerk they were denied times to hold the picnic. The paper’s representatives had attended prior events at Brookside Park and found their experience very enjoyable. After asking questions that the clerk could not answer, the clerk ushered them to the Superintendent of Parks’ office. Superintendent R. Walter Jarvis informed them that Douglass Park was the “Jim Crow Park” and he steadily insisted that Douglass Park was a nice area for its “colored citizens” (he had made the same argument in print in The Playground in 1923). The representatives from the Recorder did not obtain a permit for a picnic and were told by the superintendent that African Americans should go to Douglass Park to limit animosity. Continue reading